African-Americans at Fort Hill

Download Brochure

Download Presentation

African-Americans were a vital force in the operation and economy of Fort Hill, the home of John C. and Floride Calhoun from 1825 to 1850, Andrew Pickens and Margaret Green Calhoun from 1851 to 1871, and Thomas Green and Anna Clemson from 1872 to 1888.

Like many Southern planters of the time, Calhoun raised cotton as a cash crop using enslaved African-American labor to run his household and plantation. The Calhouns owned skilled workers such as gardeners, seamstresses and carpenters in addition to agricultural workers and field hands. Since the slaves who occupied Fort Hill left no written record, their perspective is virtually voiceless in history.

Earliest Reports

One rare documented account comes from a reporter for a New York newspaper who paid a visit to Fort Hill in 1849. He noted, “The Calhoun slaves lived approximately one-eighth of a mile from the mansion. The houses are built of stone and joined together like barracks, with gardens attached, and a large open space in front. There are perhaps 70 or 80 negroes on and about the place.”

The reporter followed Calhoun for a tour of the slave quarters. As they walked, Calhoun stopped and asked about “some who were sick; among them, seated under a cherry tree, was an aged man, who was — as he informed me — the oldest on the place, and he enjoyed particular privileges. One allowed him to cultivate four or five acres of land for cotton and other things; the proceeds of which became his property, and sometimes produced $30 to $50 a season.”

Other Calhoun slaves were also allowed to plant cotton in patches conveniently located near the quarters so they could cultivate them after their work was done. The reporter was surprised by their business savvy and wrote that the slaves were “as shrewd in getting the highest price for it (cotton) as white planters, and are as perfectly conversant about fluctuations in the markets in Liverpool and New York as a cotton broker.”

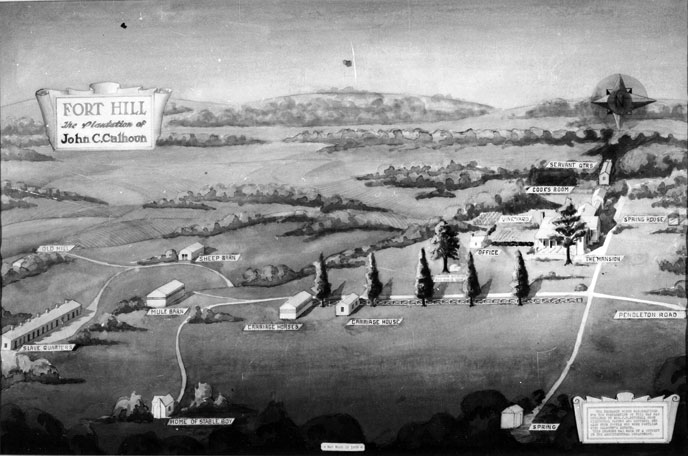

Enslaved Africans lived among their families at Fort Hill. While the reporter was visiting, he witnessed the marriage of a house slave to a female slave from a nearby plantation. He observed that the marriage ceremony was performed in the evening and in the proprietor’s mansion by the “oldest negro who was a sort of an authorized, or rather recognized, parson of the Methodist order.” After the ceremony, the excitement continued with fiddling and singing.  Shown right: Conjectural drawing of the Fort Hill plantation based on historical documents and early campus topographical maps.

Shown right: Conjectural drawing of the Fort Hill plantation based on historical documents and early campus topographical maps.

In addition to weddings, the Calhoun slaves usually had Sundays off to attend church services. St. Paul’s Episcopal and the Old Stone Presbyterian churches had slave galleries in their balconies. The longest holiday for the slaves occurred during the Christmas season when they were given additional provisions and four days off. Often the celebrations culminated with a party held in the Fort Hill kitchen.

The workforce at Fort Hill was not a homogeneous group. The ages of the Calhoun slaves ranged from infants to the elderly. The oldest recorded slave was Mennemin Calhoun. (Per tradition, all the slaves at Fort Hill were assigned the Calhoun name.) In 1849, it was reported that she was 112 years old. Her husband, Polydore, also lived a long life, and they had numerous descendants. Legend has it that Mennemin and Polydore were first-generation slaves from Africa.

Resistance at Fort Hill

Other slaves’ names are known primarily because of actions that displeased the Calhouns. Some of these were expressed in the Calhouns’ correspondence with family and neighbors. John C. Calhoun politically defended what he termed the “peculiar institution” of owning slaves in the antebellum South as “a positive good.” His paternalistic attitudes led him to believe ideas about race that supported his political ideals. However, the search for freedom led to documented accounts of Calhoun slaves who tried to liberate themselves from bondage. Three whose actions were recorded in Calhoun letters are Aleck, Sawney and Issey. Susan Clemson Richardson (pictured right) took care of the Clemson children, John Calhoun Clemson and Floride Elizabeth Clemson. This is a photo of her later in life in the Saluda area with Byron Herlong c.1880.

Susan Clemson Richardson (pictured right) took care of the Clemson children, John Calhoun Clemson and Floride Elizabeth Clemson. This is a photo of her later in life in the Saluda area with Byron Herlong c.1880.

Aleck was often the only male house slave at Fort Hill. He once “offended” Floride Calhoun and ran away in fear of punishment. When he was captured, Aleck was jailed for 10 days and given 30 lashes in order “to prevent a repetition.”

Sawney was the son of Old Sawney, a childhood companion of John C. Calhoun. Because of his father’s relationship with Calhoun, Sawney was allowed the privilege of doctor’s care. On one trip to the doctor, he set fire to the white overseer’s tent, apparently attempting to kill him. Sawney was subsequently sent to live in Alabama on the planation known as Canebrake, which was owned by Andrew, Calhoun’s eldest son.

Another child of Old Sawney, Issey was a strong-willed and defiant house slave who attempted to burn the house down by placing hot coals under a pillow in the room of another of Calhoun’s sons, William. Luckily, the smell of burning feathers floated throughout the house, and the fire was extinguished. Although described as dangerous, Issey remained at Fort Hill until freed.

Other documents record the lives of slaves who were more inclined to conform to the status quo. One such account is about a girl named Susan Clemson, who took care of Thomas and Anna Clemson’s children when the family lived at Fort Hill for a short time in the 1840s. Susan often slept in a room adjacent to the Clemsons’ room, and she later moved with the Clemsons to their home in Edgefield County, also known as Canebrake. After the war, she married Billy Richardson and moved near Saluda, S.C.

Letters and other documents show that the Clemsons took at least one slave with them to Belgium when Thomas was a diplomat from 1844 to 1851. It was recorded that the male slave Basel attracted much attention in that country because of his skin color.

Beginning in 1848, the Clemsons also had a small number of slaves at their home in Maryland — including Andy, the son of Floride Calhoun’s cook, Nelly. Before moving back to South Carolina in December 1864, Floride Clemson wrote in her diary that Andy would not be returning with them as “he was free with all Maryland negroes.”

Sale of the Estate

After John C. Calhoun’s death in 1850, his wife sold the Fort Hill estate to their oldest son, Andrew, who operated the plantation from 1850 to 1865. The inventory of the estate in the 1854 sale included a list of the property with 50 slaves in family groups. The list began with the family of Sawney (age 59) and his wife, Tilla (age 50), followed by Ned (age 25), Nicholas (age 18), Jonas (age 16), Jim (age 12), Mathilda (age 10) and Chapman (age 8). A second appraisal was performed in 1865 after the death of Andrew Pickens Calhoun, and the number of slaves had increased to 127.

Andrew Pickens Calhoun and his wife, Margaret, occupied Fort Hill during the Civil War. One account mentions a young slave boy named Rasmus who hid with 8-year-old Patrick Calhoun when Union soldiers came to the plantation.

After 1866, Floride Calhoun recovered Fort Hill through foreclosure and willed it to her daughter and remaining child, Anna Maria Calhoun Clemson. The Clemsons hired many of the former Calhoun slaves — who were freed during the Civil War — as wage hands.

One of the Clemson family’s employees was Bill Greenlee, who was 17 when Thomas Clemson died in 1888. He worked as a stable boy and carriage driver at Fort Hill during Clemson’s last years. He was later employed by the college and town of Clemson.

The Stories Don’t Stop Here

Families who worked at Fort Hill, such as the Greenlees, Frusters and Reeds, have numerous descendants still living in the Clemson area. Many were interviewed as part of the “Black Heritage in the Upper Piedmont Project,” and their stories — told through oral recordings — are deposited in the Clemson University Libraries’ Archives and Special Collections unit.

Clemson’s Department of Historic Properties conducts ongoing research to study black history and incorporate the stories about African-Americans in the narrative of the total life experience at Fort Hill.