Primary Documents: Reexamined

In 1849, a New York newspaper reporter, who paid a visit to Fort Hill, published one rare documented account of life at John C. Calhoun’s antebellum plantation. During this visit, John C. was at Fort Hill, and he and the reporter toured the plantation together. The reporter noted, “The Calhoun slaves lived approximately one-eighth of a mile from the mansion. The houses are built of stone and joined together like barracks, with gardens attached, and a large open space in front. There are perhaps 70 or 80 negroes on and about the place.”

Although some of the article contains similar factual information, like the physical location of quarters for enslaved laborers, other elements require a closer look. The reporter followed Calhoun for a tour of the enslaved field laborers' quarters. As they walked, Calhoun stopped and asked about “some who were sick; among them, seated under a cherry tree, was an aged man, who was — as he informed me — the oldest on the place, and he enjoyed particular privileges. One allowed him to cultivate four or five acres of land for cotton and other things; the proceeds of which became his property, and sometimes produced $30 to $50 a season.”

Some enslaved laborers lived among their families at Fort Hill; however, not all were able to do so. While the reporter was visiting, he witnessed the marriage of an enslaved domestic laborer to an enslaved woman from a nearby plantation. He observed that the marriage ceremony was performed in the evening and in Fort Hill dwelling house by the “oldest negro who was a sort of an authorized, or rather recognized, parson of the Methodist order.” After the ceremony, the excitement continued with fiddling and singing. There are no other documented records of other enslaved persons getting married inside John C. Calhoun’s Fort Hill. Much of the New York reporter’s account cannot be corroborated by other primary records, nor can his racial biases be ignored.

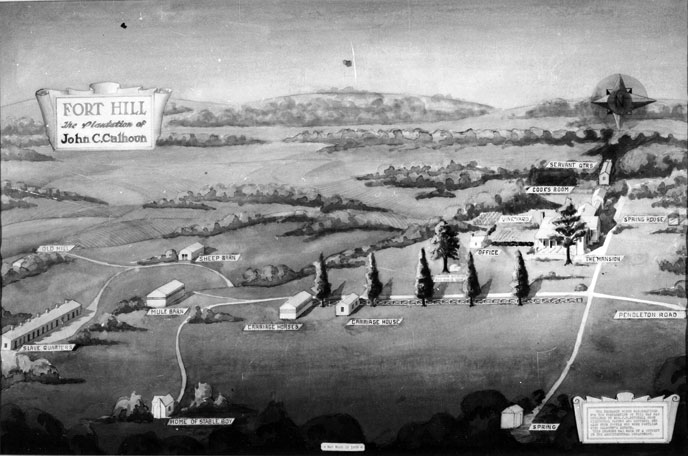

Shown right: Conjectural drawing of the Fort Hill plantation based on historical documents and early campus topographical maps.