History: USDA Vegetable Lab

“The First of Its Kind in the World”

From the onset of World War I and through the 1920s, the role of American farmers grew significantly. With much of Europe’s agricultural workforce called to war and farmlands transformed into battlefields, Europe lost much of its farm production during and after the war, creating an unprecedented increased demand in crop production across the Atlantic.

As Europe recovered in the 1920s, American farmers were left with significant inventory, resulting in falling prices for produce that only continued with the collapse of the stock market in 1929. One of the responses by Congress was the Bankhead-Jones Act of 1935 – an effort to help farmers efficiently grow sustainable and durable crops for widespread distribution.

The Bankhead-Jones Act called for the U.S. Department of Agriculture to establish nine research laboratories in major agricultural regions to “meet the necessity for creating plants … adapted to growth under certain climatic conditions and soils.” Each research station was designed to focus on the agricultural concerns of its respective region to collectively bolster America’s farming industry and contribute to national agricultural research and innovation.

The USDA vegetable breeding laboratory in Charleston County, South Carolina was the first laboratory established under this act. In February of 1936, the USDA purchased a 452-acre former phosphate mining property along Savannah Highway in Charleston for the future U.S. Vegetable Breeding Laboratory’s experimental fields. A few months later, a 3.2-acre parcel across the street previously owned by the Agricultural Society of the United States was purchased for the laboratory’s buildings from Charleston County.

The facility consisted of a small two-story, Colonial Revival-style structure with laboratories for pathology, horticulture and entomology where scientists experimented on the production of beans, corn, melons and cabbage to strengthen the truck farming industry after the collapse of the rice and Sea Island cotton industry in the Low Country.

Sprawling high ground with surrounding marsh, the property was also selected for its representation of a typical Southeastern truck-farming area where scientists could test vegetables and plants using a wide variety of soils, rainfall and temperatures that existed throughout the southeast. These conditions included frost, extreme heat and extended drought.The location also represented the South’s increasing role in American truck farming, as the accessibility to larger farming tracts and the longer growing seasons enabled the region to sustain cultivation when the northern climate became unfit for growing. Northern markets, consisting of approximately 40 million people, relied on the supply of fresh vegetables from Southern farmers.

The adjacent Truck Experiment Station, a state-run facility known today as Clemson’s Coastal Research and Education Center, and the USDA federal complex were not associated formally but would work together for decades to create more durable, healthy and vibrant crops for national distribution.

Immediately after the land purchases in Charleston, Dr. E.C. Auchter from the USDA joined members of independent and state-run plant-breeding stations from across the Southeastern states for a two-day conference at the Francis Marion Hotel in downtown Charleston to identify the most pressing issues to be addressed in the new laboratory. The conference was the nation’s first biennial vegetable breeding conference, which would continue in Charleston well into the late twentieth century.

The groundbreaking for the complex began the second week of March in 1936. The proposed complex would center around a main laboratory structure estimated at $30,000 and also include an auxiliary house with two greenhouse wings, storage buildings and workers’ cottages.

The First Experiments

By the summer of 1936, an acre was dedicated to creating disease-resistant tomatoes, ear-worm resistant corn and a half-acre for 35 varieties of zinnias. Additional plants were harvested for later experiments, including cauliflower, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, collards, watermelon and radishes. The staff also received 220 pounds of onion bulbs from the University of California to develop onions resistant to mildew.

With the nearly 50 acres already cultivated for the laboratory’s first experiments, local contracting firm Dawson Engineering was hired in the summer of 1936 to construct the laboratory and accompanying structures. During the next six months, Dawson Engineering constructed the multiple building complex that would become the first USDA research facility to collectively have a laboratory, greenhouse and experimental fields. As Dawson Engineering served as the complex’s construction team, the laboratory and its auxiliary buildings were most likely designed by the USDA’s architects.

By the time of the laboratory’s completion in early 1937, new crops of snap peas, cabbage, watermelons, tomatoes and sweet corn were ready for testing. In addition to these crops, the U.S. Division of Plant Exploration and Introduction sent several new and “valuable and economic and ornamental plants showing promise of usefulness” from foreign countries to the “new vegetable breeding project” in Charleston for analysis.

Margaret “Peggy” Kanapaux Sullivan, a Charleston native with a biology and English degree from the College of Charleston, served as a biochemist on the property until 1942, at which time she left for active duty as part of the WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service). During her tenure at the laboratory, Sullivan worked with other property scientists to create “winter hardy” cabbage, high-quality snap peas, disease-resistant tomatoes and durable watermelons, which would take years to master. Sullivan would later return after the war.

In 1938, Illinois horticulturist Charles Frederick Andrus joined Dr. Wade, Dr. Poole and Sullivan as part of the laboratory’s staff and was tasked with further studying diseases in beans, watermelons, tomatoes and cabbage. This marked the beginning of Andrus’ 30-year employment at the laboratory, during which time he ultimately would create several new breeds of watermelon and tomatoes.

The staff continued to breed severe weather and bacteria-resistant snap beans, experimented with maintaining quality in flavor and durability through drying and preserving seeds and even tested fertilizers and irrigation systems. They worked to create more colorful and sweeter watermelon, bigger potatoes and redder tomatoes.

By 1943, Louisiana scientist Dr. James E. Welch was hired to test quick freezing and dehydration qualities of crops to improve the “shipability” and preservation of vegetables during a time of vast food rationing. Within the next year, Charleston's Evening Post reported that the laboratory mastered the flavor-saving, quick-freeze method and was prepared to help provide “more and better food” to Americans. By 1945 the staff consisted of scientists ranging in expertise from genetics, cytology, pathology, physiology and chemistry in horticulture, vegetable composition and related fields.

In the post-war period, the staff worked on creating more disease-resistant snap peas with “more color,” cabbage with higher vitamin content and “greater penetration of green color into the head,” darker green peas with a “more attractive appearance,” larger ears of corn with greater resistance to earworm, larger tomatoes with “high color” and resistance to cracking and watermelons with a “very attractive appearance.”

“A more prosperous South, a better-fed North”

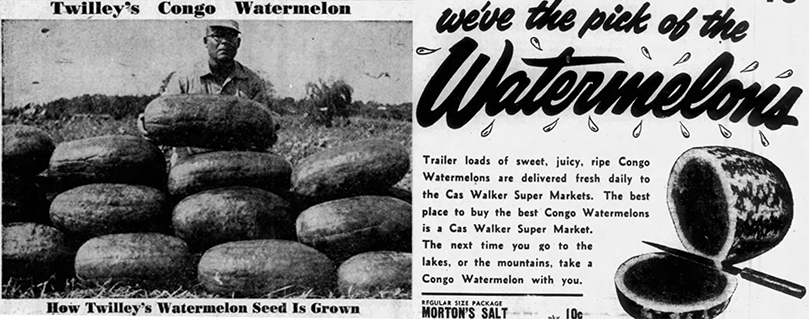

In 1949 the laboratory finalized a new watermelon breed called the Congo, which was bred from what the Miami News called “a vastly superior specimen” from Africa and made to have a sweeter taste and a tough rind for shipping. After its first shipments, the Congo, often referred to as “the king of all watermelons,” was widely distributed and replaced the popular Garrison and the Cannonball varieties.

As the 1950s dawned the Charlotte Observer reported that Charleston’s vegetable breeding led to “a more prosperous South and a better-fed North,” crediting the Congo watermelon and the Contender, a “fresh market” snap pea with great tolerance to heat and drought, as examples of the national advances in vegetable farming that could be traced to the complex.

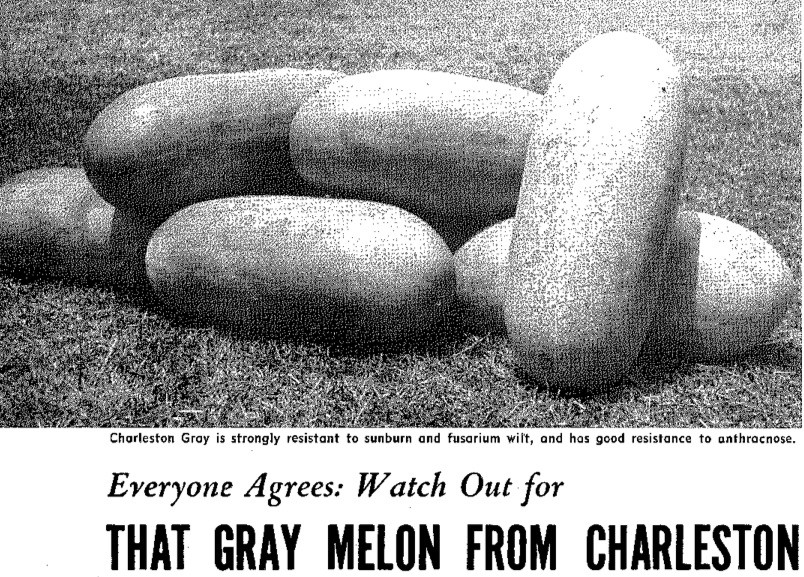

Within the next three years, the laboratory introduced the Bush snap bean, followed by the Homestead tomato and the Fairfax watermelon. By 1954, the Charleston Grey (or Gray) Watermelon was introduced, a worldwide commodity for which Dr. Andrus received the USDA Superior Service Award and was elected into the American Society of Horticulture Hall of Fame in 2002.

Although Hurricane Gracie and the subsequent mildew destroyed much of the cabbage crop in 1959, Dr. James C. Hoffman successfully introduced a new variety of snap beans to the American farmer in 1960 called the Extender. The new bean became known for its wide adaptability to climates.

Amidst persistent corn, tomato, cabbage and bean farming and testing, advances in melons continued throughout the next decade. After a sixteen-year trial, the Summerfield watermelon was released in 1969 and was a cross between the Fairfax and the Blackstone. It was designed for superior wilt resistance, its large size and high-quality flesh.

The laboratory produced new types of turnips and collards resistant to common disease and cold with the adjacent Clemson University Truck Experiment Station in 1977 after a 15-year developmental stage and also started a new sweet potato breeding program.

In 1980, a one-story warehouse was added to the complex to accommodate new research that focused on weed science.

The laboratory often housed education and research groups to demonstrate the experiments on ongoing research. In addition to local agricultural societies and national scientists, students Folbert Bronsema and Sjaan VanEghmaal from the University of Wageningen in Netherlands, for example, spent five months at the laboratory in 1987 to learn how to breed flowers for their return to Holland. A chemist from India and another Dutch student were also scheduled to spend months training at the facility that year.

In 1990, USDA received $5 million to begin work on a new shared laboratory with the Clemson Truck Experiment Station, known by the 1980s as the Coastal Research and Education Center, yet construction of a new, 54,000 square foot, $20.5 million facility did not begin until in 1999. In the meantime, the laboratory produced the Charleston Greenpack, a pinkeye-type southern pea with significant field resistance to disease and a vibrant green color, after a seven-year trial. The Charleston Belle, a disease-resistant bell pepper, was also released in 1997.

By 2003, the new research facility was completed across the street with office space for twenty scientists from both USDA and Clemson laboratories. Building 1 and Building 2 were abandoned at this time and no new work has taken place on the site since. At the former complex’s closure, the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service reported that the laboratory developed and released more than 160 vegetable varieties since its opening. Notables included the Charleston Gray, Congo, Garrisonian, Graybelle, Fairfax, and Summerfield watermelons, Planters Jumbo and Mainstream muskmelons, Charleston Green pack southern peas, Wade, Bonus, Extender, and Provider snap bean, Homestead tomato, Charleston Hot pepper, and Charleston Belle bell pepper.

In 2015, the original laboratory complex was deemed eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A (Historic Events) for its national associations with the USDA’s 1930s expansion of its research capabilities to assist farmers in efficiency by producing goods across the country, developing new breeds more adaptable to the region through the creation of pest-resistant strains that allowed farmers to increase crop yields, and for its regional association with the improvement of truck-farming produce in the southeast region of the United States from 1936 through 1980.

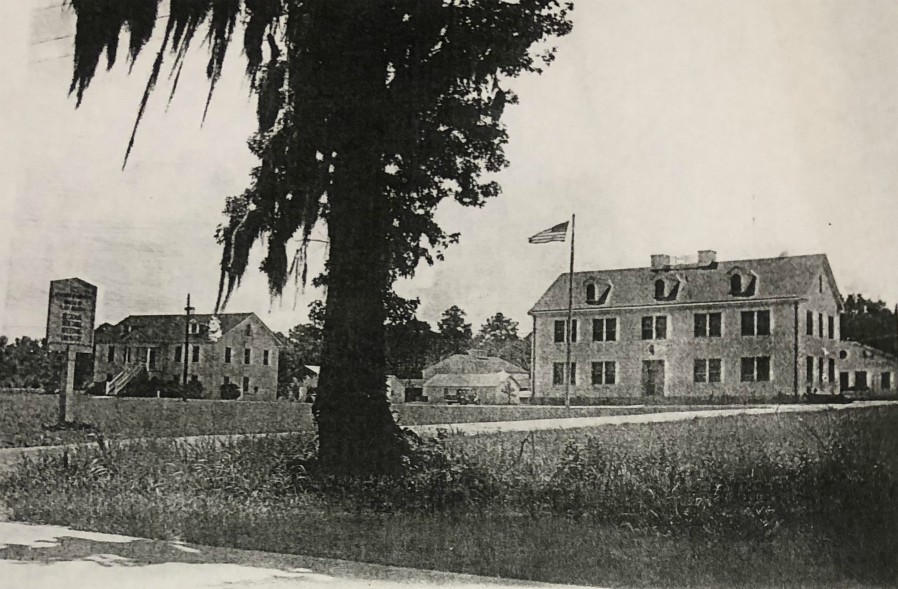

USDA Vegetable Lab building in 1945

Southeastern territory represented by the U.S. Vegetable Breeding Laboratory in Charleston County (USDA, 1945)

1940s photograph showing USDA laboratory complex (right) and Truck Experiment Station (left) (USDA, 1945)

1950 photograph of Peggy Sullivan on the front steps of Building 1 (USDA,1950)

1955 April 15,The Daily Times, Salisbury, Maryland; (right) 1955 July 21,The Knoxville Journal, Knoxville, TN

1954 announcement for the Charleston Gray Watermelon(USDA, 1954)

Building 1 North (primary) facade

Building 2 Overview of greenhouse complex, looking south

Building 1 and Building 2 - Facing Southeast

Building 1 South Elevation - Facing North

The text in this website is adapted from U.S. Vegetable Breeding Laboratory Former U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Southeastern Vegetable Breeding Laboratory, A History and edited for clarity.