History of the African American Burial Ground

The history of the African American Burial Ground on what is now the Clemson University campus spans centuries and generations. It is a history of individuals, families, and communities who lived, worked, and died on this land, from the era of enslavement in the antebellum period to the era of Jim Crow segregation in the early 20th century. African and African American enslaved persons, sharecroppers, tenant farmers, domestic laborers, convicted laborers, as well as wage workers and their families are all believed to be buried in unmarked graves on this sacred site.

The Antebellum Era

The antebellum era was a period in American history characterized by the expansion of slavery, which had existed in the American colonies for about two hundred years. Slave traders and others engaged in the business of slavery forcibly migrated millions of men, women, and children from their homes in Africa and, after the grueling Middle Passage, sold them at port cities like Charleston. Lifelong, heritable enslavement was inflicted upon people of African descent, who labored in rural and urban areas throughout America. Following the American Revolution, the economic and geographic expansion of the United States coincided with the expansion of slavery and the domestic slave trade. As white settlers and enslavers sought to increase agricultural production in new lands from the Louisiana Purchase, Indigenous nations, such as the Cherokee in Upstate South Carolina, were displaced and removed. By the early 19th century, short-staple cotton had become the main crop of the country, especially in the South, due in part to the new technology of the cotton gin. Enslaved people on southern plantations cultivated cotton, which was then transported to mills for textile production and exported into the global market economy. By 1860, prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, approximately 4 million people were enslaved in the United States, 400,000 of whom were enslaved in South Carolina.1

The Enslaved Community at Clergy Hall

In 1801, Reverend James McElhenny moved onto the land that would later become the Fort Hill Plantation and Clemson University. He worked as a minister at Old Stone Church, which still stands today. According to the 1810 federal census, McElhenny enslaved 25 African Americans who farmed the land and likely built Clergy Hall, which was the four-room house where McElhenny and his family lived. Reverend McElhenny died in 1812, and Floride Bonneau Colhoun purchased the land. We do not know if those who were enslaved at Clergy Hall are buried on Cemetery Hill. Carrel Cowan-Ricks, the archaeologist who studied the African American burial ground in the early 1990s, noted, "we cannot ignore the potential that a number of graves may well include the bondsmen and women of Rev. McElhenny."2

Carol M. Highsmith, The Old Stone Church in Clemson, South Carolina, 2017, Library of Congress.

Floride Calhoun and Cornelia Calhoun, "A Schedule of Slaves with their names and ages," in Deed to Fort Hill Plantation, May 15, 1854, Mss 2, Box 1, Folder 25, Thomas Green Clemson Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

The Enslaved Community at Fort Hill Plantation

More than 139 African and African American men, women, and children were enslaved by the Calhoun and Clemson families at the Fort Hill Plantation, as well as other plantations in South Carolina and Alabama and a mine in Georgia, from 1826 to 1865. At Fort Hill, US Vice President John C. Calhoun and his family required these individuals to plant and harvest crops such as wheat, cotton, rice, and oats in outlying fields, and to take care of livestock. Enslaved men, including Tom and Daniel, were tasked with constructing buildings and furniture. Enslaved women labored as cooks, nurses, and domestics in the house. Daphne, Nelly, Katy, and Peggy nursed the white Calhoun and Clemson women and their children. They may have also been the caretakers for enslaved families at Fort Hill.

The enslaved community at Fort Hill nurtured extensive social and family relationships. Though marriages among enslaved people were not legally recognized, many people were married, including Sawney and Tilla and Daniel and Rosanna. Many children were also born and lived with their parents at Fort Hill. Children were often named after their parents, grandparents, and other family members. These relationships show personal agency and generational connections and endurance despite enslavement. For instance, Fanny, the child of Daniel and Rosanna, named one of her own children Daniel after his grandfather. Sawney and Tilla had eight children, including Sawney Jr. who ran away from Fort Hill on at least one occasion, resisting his enslavement.

Those who were enslaved at the Fort Hill Plantation also maintained ties with enslaved people at nearby plantations; Fort Hill was not an isolated place. The Lewis family’s plantation was just to the south and east of Fort Hill, and the Colhoun’s Keowee Plantation was just across the Seneca River to the north. Also nearby was the Pickens family’s Hopewell Plantation. In 1855, Henry E. Ravenel bought Seneca Plantation on the opposite bank of the Seneca River from Fort Hill. Enslaved people at neighboring plantations may have met with each other at night and on Sundays, shared news and food, cared for each other and married, and even had children together. The burial ground at Fort Hill might have been a community cemetery, a sacred place where enslaved people across different plantations gathered to bury their loved ones.

Death rates for adults and children were relatively high in the 19th century, especially for people who were enslaved on southern plantations with inhospitable and unsanitary living conditions. Common illnesses included colds, edema or dropsy, respiratory illnesses, and fevers. Women died in childbirth, including Sophia who passed away in 1850 and Nelly who died in 1856. Children and infants often died from infectious diseases such as measles and whooping cough and from parasitic worm infections. In 1850, the same year that John C. Calhoun passed away from pneumonia, at least three children died at Fort Hill. Aleck, who was 12 years old, passed away from an unknown infection. John, who was only two years old, died from worms, and Elizabeth, who was also two years old, died from whooping cough. Between 1864 and 1865, the last year of the Civil War, an unimaginably painful tragedy occurred at Fort Hill. About 70 enslaved people died, the majority of whom were infants and children who succumbed to measles and whooping cough.3

The Reconstruction Era

Just prior to the end of the Civil War in March 1865, Andrew Pickens “A.P.” Calhoun, the oldest son of John C. Calhoun and owner of the Fort Hill Plantation, died unexpectedly. An inventory of his property was soon completed to determine how to satisfy his debts, including the mortgage on the plantation that he had not paid since purchasing the property from his mother in 1854. The inventory included 139 African Americans classified as enslaved, though they were technically free due to the Emancipation Proclamation that went into effect on January 1, 1863. About that time, A.P. Calhoun’s niece Floride Clemson reported that only 15 formerly enslaved persons remained at Fort Hill.

Beginning in 1866, freedmen, freedwomen, and children began laboring at Fort Hill as sharecroppers for the Calhoun and Clemson families. Initially, they affixed an X mark between their first and last names for a signature on formal printed contracts administered by the Freedmen’s Bureau. On December 27, 1866, 38 freedmen and freedwomen signed contracts to work for Duff Green Calhoun, the eldest son of Andrew Pickens Calhoun, one for 37 laborers and the other for one laborer. In exchange for planting and harvesting crops at Fort Hill, they would receive a share of the crop and wages. The contract also included a legal mechanism for the recovery of their wages in case Duff Calhoun reneged on his part of the agreement.

However, the freedmen and women who agreed to labor for Thomas Green Clemson at Fort Hill between 1868 and 1874 affixed an X mark between their first and last names for a signature on handwritten contracts that included some of the articles of agreement contained in the Freedmen Bureau’s contracts for sharecroppers but also stipulated additional labor requirements likely devised by Clemson. Additionally, the contracts Clemson utilized did not include any legal recourse for the sharecroppers should he or his agent fail to keep their end of the agreement.

Several African American tenant farmers also signed contracts to work for Thomas Green Clemson at Fort Hill, some of whom had been enslaved at the plantation.

Additionally, Thomas Green Clemson employed African Americans to labor as domestics in his household. According to the 1870 US Census, six African Americans were living with the Clemsons: 30-year-old Mahalie Clemson, employed as the cook, and 25-year-old Betsy Moultrie, a house servant, and her children 9-year-old Fannie, 8-year-old Anna, 4-year-old Eddy, and 2-year-old Robert.4

Thomas Green Clemson, Articles of agreement between Thomas G. Clemson and freedmen and women, January 1, 1871, Mss2, Thomas Green Clemson Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

The Jim Crow Era

Named for a popular minstrelsy character, the “Jim Crow” era was the Southern reaction against the expansion of African American civil rights during Reconstruction. Former Confederate states passed local and state laws called “Black Codes” that restricted the movement of Black people, limited where they could live, work, or attend school, and reinforced white supremacy and the paternalist society that had existed prior to the Civil War. Discriminatory laws became codified and revised in state constitutions and were upheld by the Supreme Court in 1896 with Plessy v. Ferguson, which established the doctrine of “separate but equal.” Race-based segregation was legal until 1954 and the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Supreme Court ruling.

Convicted laborers stand before the corn crib at Clemson College, ca. 1904. Series 100, Clemson University Historical Photographs, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

Convicted Laborers

Between 1890 and 1915, Clemson trustees leased mostly African American convicted laborers ages 14 to 67 from the South Carolina state penitentiary to help build and maintain the college. The convicted laborers cleared land, made millions of bricks, erected buildings, planted and harvested crops, built dikes, and made roads and sidewalks. During the post-Reconstruction era, white lawmakers, primarily in the South, had expanded the convict leasing system by exploiting a provision in the Thirteenth Amendment that allowed for “involuntary servitude” for the commission of a crime. On June 8, 1877, South Carolina legislators began passing bills that codified leasing as a profitable means to employ felons and soon authorized the building of the state’s first penitentiary. African Americans were disproportionately convicted of felonies ranging from loitering to petty theft and given sentences ranging from a few months to life. South Carolina leased primarily African American convicted laborers to businesses and individuals throughout the state. The Clemson Board of Trustees used convict leasing to hire cheap labor in building the college, including Hardin Hall, Trustee House, Old Main, and Sikes Hall that are still part of the built landscape. By 1915, however, they discontinued the use of convicted laborers when the system was no longer cost effective. At least twelve African American convicted laborers died while working at Clemson and are believed to have been buried on the west side of Cemetery Hill that later became Woodland Cemetery.5 Although the trustees stopped leasing convicted laborers in the early 20th century, some Clemson employees later leased prisoners from county jails to work at the T. Ed Garrison Arena. When the use of convict labor came to light, Clemson administrators required its discontinuation on all university-affiliated sites throughout South Carolina.

Convicted Laborers Who Died at Clemson

Furman Jones - died May 24, 1891

Perry Abraham - died May 28, 1891

John Dacus - died June 20, 1891

Albertus Moore - died June 20, 1891

Levi Elmore - died September 2, 1891

Charles (Charley) Tompkins - died May 12, 1893

William Johnson - died May 17, 1893

Julius Clinkscales - died December 11, 1893

Sam Barber - died December 18, 1900

Ben Collier - died February 8, 1902

William Smalls - died May 11, 1902

Charley McCarthy - died May 8, 1907

A man stands near field stones in an unidentified area of Cemetery Hill, ca. 1950s-1960, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries. The field stones might have marked where convicted laborers were buried in Cemetery Hill.

Wage Workers at Clemson

and Forced Segregation

When Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina opened in 1893, many of its students and employees lived on campus. The 1900 US Census documented Clemson College as an integrated community where white and Black employees lived next door to each other on campus and 25 convicted laborers who were helping to build the college were housed in a stockade.

In the early decades of the 20th century, Clemson College moved from providing housing for both white and African American employees in the same neighborhoods to segregating employees in separate racialized housing clusters. By 1930, African American employees, many of whom worked on the college farm or as servants, lived in a segregated community on Oak Lane, a short street that was previously located where the Strom Thurmond Institute was later built. A second segregated community for African American wage workers and their families was located on Riverside Drive located near Sirrine Hall.6

Despite college administrators’ efforts to segregate and marginalize African American employees and their families, members of the faculty Buildings and Grounds Committee advocated for the inclusion of some African American history on the built landscape. In 1946, they recommended that a street be named for Sawney Sr., John C. Calhoun’s “favorite” enslaved person. The administration approved the recommendation. A street adjacent to Sawney’s branch (a creek) where Sawney Sr.’s cabin was believed to be located was selected. However, by 1970, the street had been renamed Kappa Drive.7

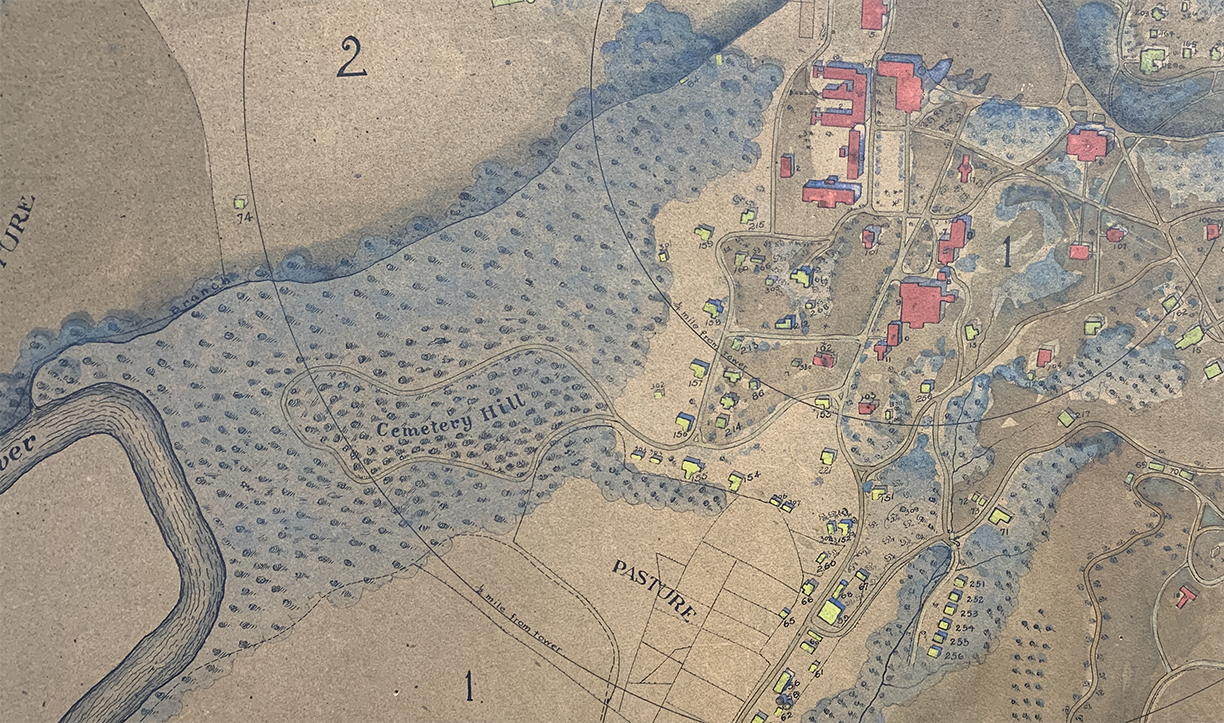

Map of Clemson College, 1920, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries. Houses numbered 301 to 331 were labeled as "servant houses" on a 1914 map. Houses numbered 302 to 309 were near Riverside Drive and were the closest to Cemetery Hill. Houses numbered 254 to 259 were located near Sawney's branch.

The Tiger (Clemson, SC), January 8, 1953. A photograph from the 1953 Tiger newspaper shows African American employees who worked in the laundry, mess hall, and barracks. Special thanks to CI Team Member Gillian Barnard for this source.

To learn more about African American history at Clemson University, visit the Call My Name website.

By the early 1940s, Clemson College had segregated African American employees who worked in the mess hall, or dining hall, to a neighborhood that would become known as “the Bottoms” or "the River." It was an area of campus that was located on the northwest slope of Cemetery Hill, just to the west of Memorial Stadium and to the east of the Seneca River. This area was prone to flooding and muddy conditions. There were nine houses in the Bottoms, some of which were built on stilts to prevent the houses from flooding.8 As many as three families lived in one house. One family who likely lived in the Bottoms was that of Louis and Dessie Lagree Martin and their children. Louis Martin worked in the mess hall at the college, and his wife Dessie was a granddaughter of Nancy Washington Lagree, who was formerly enslaved at Fort Hill. Viola Williams, Dessie’s sister, recalled in an oral history interview that the Martin, Dupree, and Whitt families lived near the area of the stadium.9

By the mid 1950s, families had moved out of the houses in the Bottoms, as the college was worried about potential flooding from the US Army Corps of Engineers' Hartwell Dam project. Clemson was also in the process of segregating African American employees and their families completely off campus in a new housing project called the Tom Littlejohn Homes under the National Housing Act. Clemson then removed the houses in the Bottoms, cleared the trees, and turned that area into a parking lot for Memorial Stadium in the summer of 1960.10

Aerial View of Clemson Campus, ca. 1940s, Series 100, Clemson Historical Photographs, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries. Some of the houses in the Bottoms are visible through the trees to the west of Memorial Stadium.

Memorial Stadium construction showing houses in the Bottoms, ca. 1941-42, C. Y. Thomason Construction Company Archive. Special thanks to CI Team Member Jermaine Johnson for this photograph.

Citations

- Eighth Census of the United States, Pendleton, South Carolina, 1860, Bureau of the Census, M653, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Ancestry.com, 1860 U.S. Federal Census - Slave Schedules [database on-line], (Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010).

- Third Census of the United States, Pendleton, South Carolina, 1810, Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, M252, Roll 61, page 235, image 00285, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Ancestry.com, 1810 United States Federal Census [datatbase on-line], (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2010); Carrel Cowan-Ricks, “Cemetery Hill Archaeological Project,” South Carolina Antiquities 24, nos. 1 & 2 (1992), 22.

- Julia Wright Sublette, “The Letters of Anna Calhoun Clemson, 1833-1873,” Thesis (Ph. D.) Florida State University, 1993; Floride Calhoun and Cornelia Calhoun, “A Schedule of Slaves with their names and ages,” in Deed to Fort Hill Plantation, May 15, 1854, Mss 2, Box 1, Folder 25, Thomas Green Clemson Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/210; Rhondda Robinson Thomas, Call My Name, Clemson: Documenting the Black Experience in an American University Community (Chicago: University of Iowa Press, 2020); Mary Stevenson, ed., The Diary of Clarissa Adger Bowen Ashtabula Plantation, 1865 (Pendleton, SC: Foundation for Historic Restoration in Pendleton, 1973), 96-97; 1850 Mortality Schedule for Pickens District, South Carolina, US Federal Census Mortality Schedules, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Accessed through Ancestry.com; Floride Clemson, A Rebel Came Home; the Diary of Floride Clemson Tells of Her Wartime Adventures in Yankeeland, 1863-64, Her Trip Home to South Carolina, ed. Charles M. McGee, Jr. and Ernest M. Lander, Jr. (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1961), 90-91; Ernest M. Lander, The Calhoun Family and Thomas Green Clemson: The Decline of a Southern Patriarchy (Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press, 1983). Undergraduate students Lucas DeBenedetti, Aimey Jimm, and Robin Urban in the Fall 2021 Creative Inquiry class for the cemetery contributed to this research.

- Floride Clemson, A Rebel Came Home, 93; Thomas Green Clemson, Articles of Agreement between Thomas Green Clemson and freedmen and women, 1867, Box 5, Folder 4, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1133/; Articles of Agreement between Thomas G. Clemson and freedmen and women, January 1, 1868, Box 5, Folder 5, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1134/; Articles of Agreement between Thomas G. Clemson and freedmen and women, January 1, 1871, Box 5, Folder 7, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1159/; Articles of Agreement between Thomas G. Clemson and freedmen and women, January 1, 1874, Box 5, Folder 10, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1189/, Articles of Agreement between Thomas Green Clemson and Robert Butler, October 1874, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1206/, and Articles of Agreement between Thomas Green Clemson and William Johnson, December 1874, Box 5, Folder 11, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/tgc/1209/, all in Mss 2, Thomas Green Clemson Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries. Duff Green Calhoun, Agreement between D. G. Calhoun and freedmen and women, December 25, 1867, and Agreement between D. G. Calhoun and Fee, December 27, 1867, in Records of the Field Offices for the State of South Carolina, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1865-1872, Series M1910, Reel 45, Record Group Number 105, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (Lehi, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2021). “This agreement, made between John C. Calhoun of Pickens District, State of South Carolina and Wash,” Records of the Field Offices for the State of South Carolina, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1865-1872, Series Number: M1910; Reel Number: 50, Record Group Number: 105, Ancestry.com, U.S., Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865-1878 [database on-line] (Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2021), 503-04; “This agreement, made between John C. Calhoun of Pickens District, State of South Carolina and Harriet, Jim, Peter, and Abb,” Records of the Field Offices for the State of South Carolina, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1865-1872, Series Number: M1910, Reel Number: 45, Record Group Number: 105, Ancestry.com. U.S., Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865-1878 [database on-line] (Lehi, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2021), 78-79.

- Annual Reports of the Board of Directors and Superintendent of the South Carolina Penitentiary, Reports and Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina at the Regular Sessions, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC.

- Twelfth Census of the United States, Clemon Agricultural College, Seneca, Oconee County, South Carolina, 1900, T623, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census [database on-line], (Provo, Ut, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004); An Insurance Map of Clemson, ca. 1914, Mss 81, Tillman Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

- Minutes of Faculty Senate Meeting, September 16, 1947, Series 36, Box 26, Folder 7, Faculty Senate Records, 1894-1988, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/faculty_senate/10

- David J. Watson to J. C. Littlejohn, June 6, 1942, Series 87, Box 26, Folder 6, Office of the Vice President for Business and Finance Records, Correspondence, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries; F. R. Sweeny, H. E. Glenn, C. C. Norman, I. A. Trively, and F. R. Sweeny, An Atlas of Clemson College Properties, 1945, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

- Sixteenth Census of the United States, Clemon Agricultural College, Seneca, Oconee County, South Carolina, 1940, T627, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Ancestry.com, 1940 Federal Census [database on-line], (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2012); Viola Williams, Transcript of an oral history conducted in 1990, Mss 282, Black Heritage in the Upper Piedmont of South Carolina Project Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries. This research was conducted by undergraduate students in the Fall 2021 Creative Inquiry class: Gillian Barnard, Abbigayle Stewart, and Nolly Swan.

- Meeting Minutes of the Board of Trustees, Clemson Agricultural College, August 5, 1949, Clemson University Libraries, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1545&context=trustees_minutes; Robert F. Poole, President's Report to Board of Trustees, 1949, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/pres_reports/48; Aerial Photographs of the Clemson Campus, 1960, University Facilities, Clemson University.