History of Woodland Cemetery

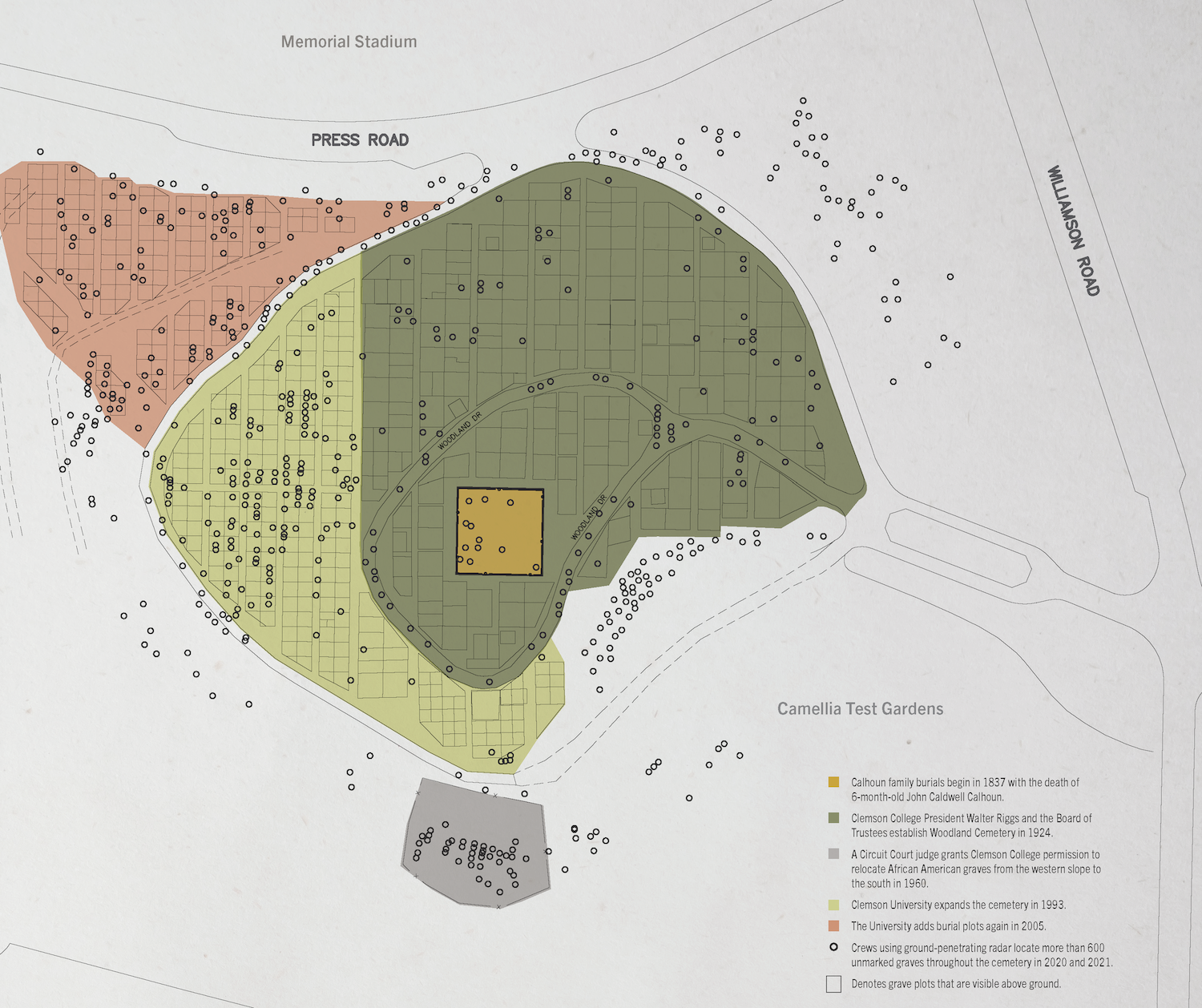

The Clemson Board of Trustees established Woodland Cemetery near the Andrew Pickens “A.P.” Calhoun family plot in 1924 for white faculty and officers of the college. Trustees have expanded the cemetery significantly since the first outline of plots was completed over 100 years ago. Additionally, throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, campus development and other projects have impacted the size and scope of the cemetery and surrounding landscapes. Woodland Cemetery is the final resting place for over 600 Clemson employees and their immediate families.

Establishment of Woodland Cemetery

Clemson President Walter M. Riggs proposed establishing a faculty cemetery on campus during the July 1922 Clemson Board of Trustees meeting. After the trustees approved the idea, President Riggs assembled a Cemetery Committee, composed of faculty members, whose goals were to find a suitable location and determine a plan of care for the cemetery. In May 1923, "after a careful consideration of various proposed sites," the Cemetery Committee informed Riggs of their recommendation that “the best available location is what is now known as ‘Cemetery Hill’ adjacent to the Calhoun plot.”1 It is not known what other sites the committee considered.

The development plans for the new cemetery were underway when President Riggs died suddenly on January 22, 1924, at a meeting with administrators of other land grant institutions in Washington, D. C. Clemson administrators asked his wife Lula Mae Moore Riggs via telegram whether he should be buried in his hometown of Orangeburg, at the Old Stone Church cemetery near Clemson College, or on the college grounds, even though the faculty cemetery had not yet been established.2 Three days later, President Riggs was buried in a grave on the eastern side of Cemetery Hill, the first white Clemson employee to be buried in that site.

Map of Clemson College Lands, 1920, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

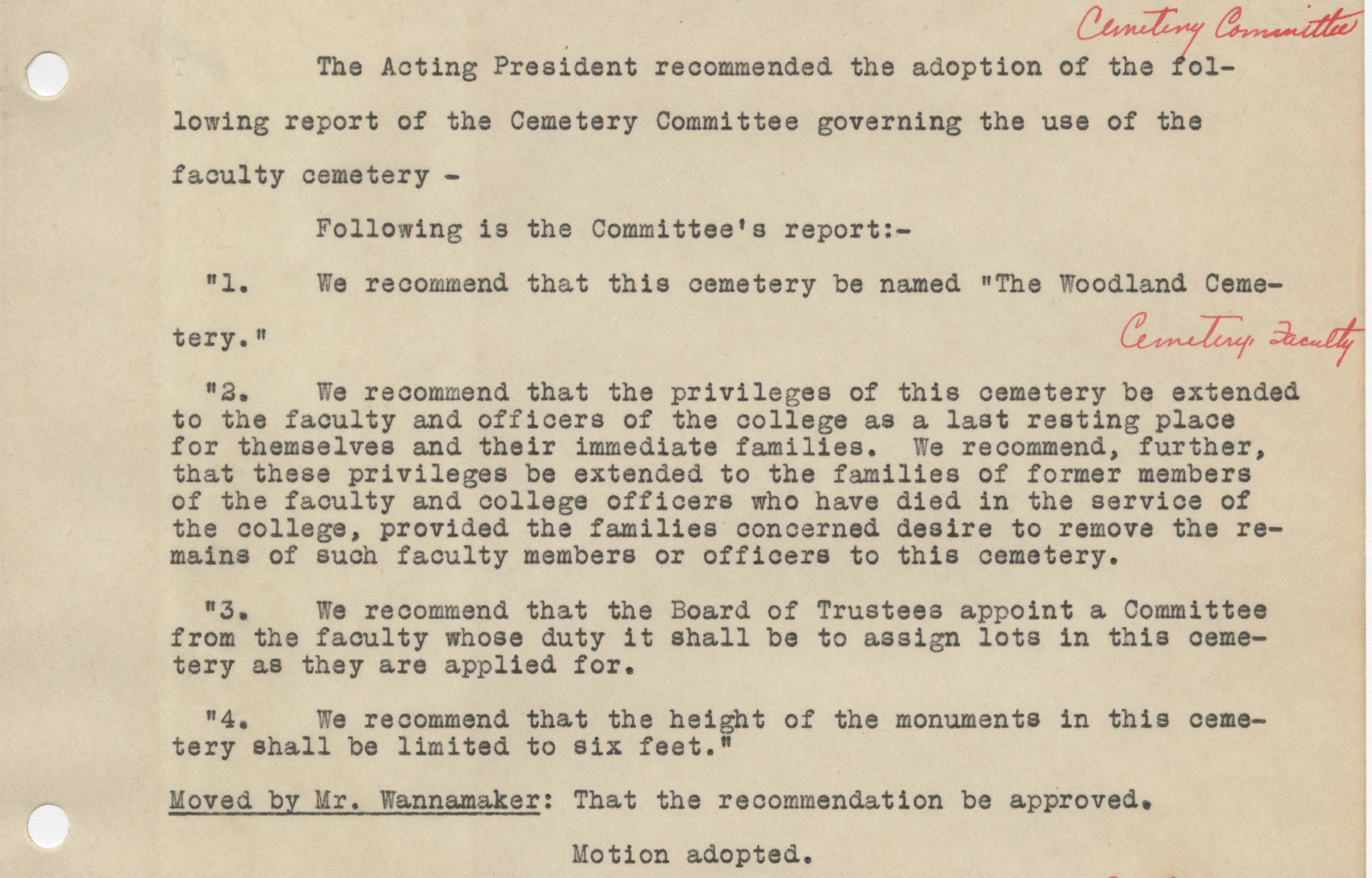

Clemson Board of Trustees Meeting Minutes, July 10, 1924, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

The Clemson Board of Trustees officially established Woodland Cemetery on July 10, 1924, for “officers and faculty of the college as a last resting place for themselves and their immediate families.”3 Samuel Maner Martin, a math professor and chairman of the Cemetery Committee, initially assigned plots in Woodland Cemetery. In 1938, civil engineering professor H. E. Glenn surveyed the area and expanded the number of plots to 202. The majority of plots at that time were 20 feet by 20 feet and could hold eight burials. In 1954, Clemson created the first official "Woodland Cemetery Lot Assignment" certificate. Plots in Woodland Cemetery have always been free of charge.4

Many prominent figures in Clemson history are buried in Woodland Cemetery, including football coach Frank Howard, Clemson's first history professor William S. Morrison, engineering professor and dean Samuel B. Earle, coach and secretary of the Clemson YMCA Preston Holtzendorff, as well as every deceased Clemson President since Walter Riggs.

Campus Expansion and Development

Memorial Stadium

The college landscape, particularly west campus and the cemetery, were significantly transformed in the 20th century. By the 1930s, Clemson's continued success at football meant that the stands at Riggs Field, where the team was playing, could no longer accommodate the growing number of students, faculty, alumni, employees, and local residents attending games. Professor H. E. Glenn established plans for a new football stadium to be built to the north of Woodland Cemetery in 1941.

The site of the current stadium was selected because it sat in a natural ravine, suitable for bowl seating. Football team members cleared the site, and the construction company of C. Y. Thomason built the structure. It allowed for 20,000 seats and areas for parking. The first game in the new Memorial Stadium was played on September 19, 1942.5 It is unknown whether any unmarked graves were located in the area where the stadium was built and then destroyed by construction.

Building Memorial Stadium at Clemson near Cemetery Hill, 1941-42, C. Y. Thomason Construction Company Archive. Special thanks to CI Team Member Jermaine Johnson for this photograph.

Explore Cemetery Hill Before and After Memorial Stadium

Aerial Photograph of Campus in 1938, Courtesy of Clemson Agricultural Services and Experimental Forest Department.

Aerial Photograph of Campus in 1944, Courtesy of Clemson University Facilities.

Hartwell Dam and the 1960 Court Order

In the succeeding decades, campus development and federal projects impacted the area of Cemetery Hill on which Woodland Cemetery was located. The US Army Corps of Engineers wanted to build Hartwell Dam in the region mainly to provide hydroelectric power and flood control. The original plan for the project would have flooded the western part of the Clemson campus, including Memorial Stadium and the agricultural bottomlands.

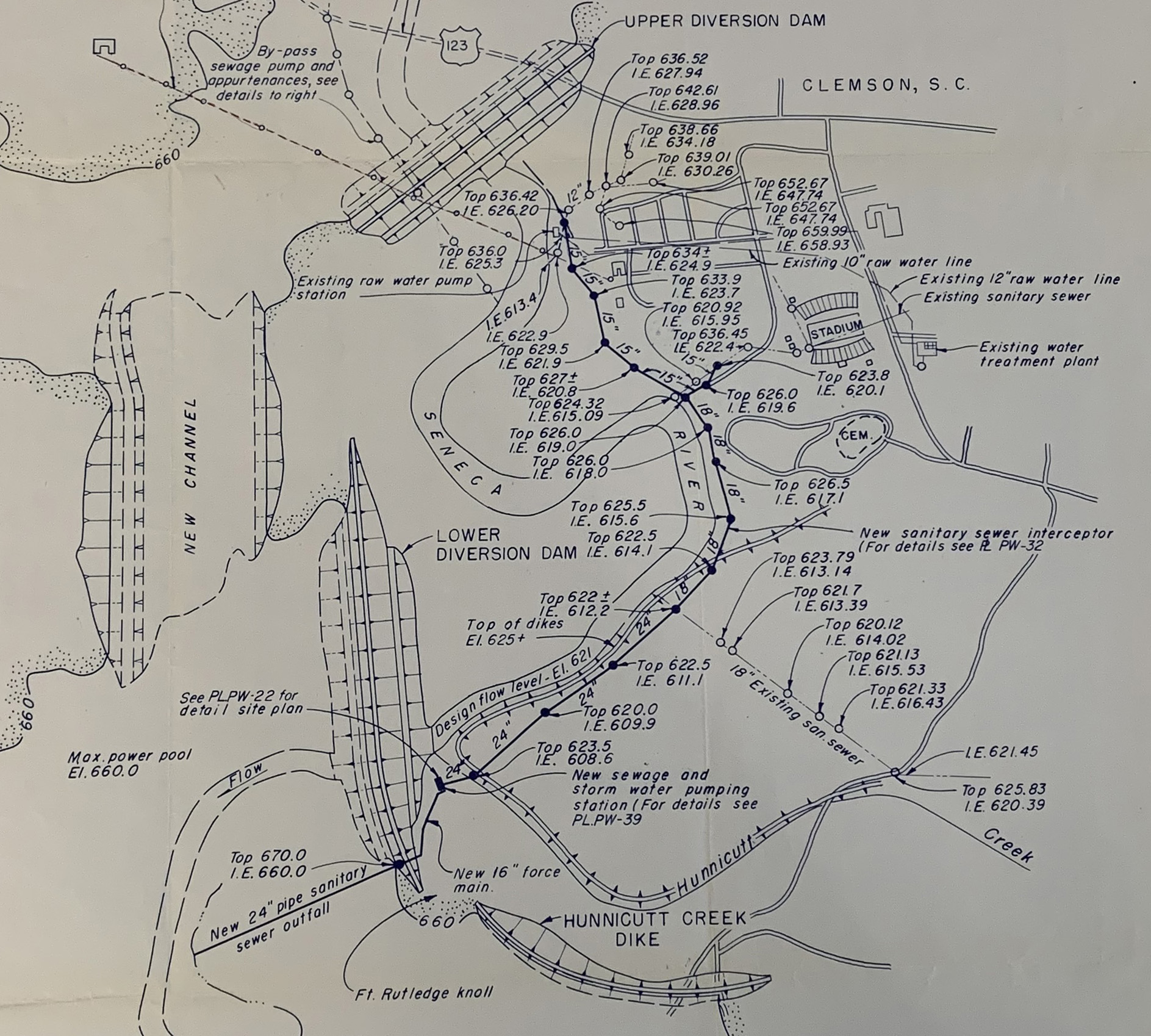

Eventually, a plan was devised by 1959 that involved the construction of two dikes, or diversion dams, to cut off the Seneca River and protect the campus from flooding. The upper dike would be located near the Esso Club, and the lower dike would be built near Fort Rutledge. The Army Corps of Engineers contracted the project out to the Nello L. Teer Company in the summer of 1960. On August 19, 1960, a civil engineer drew a topographical map of the lower, western part of Cemetery Hill and included plans for reinterment of burials.6

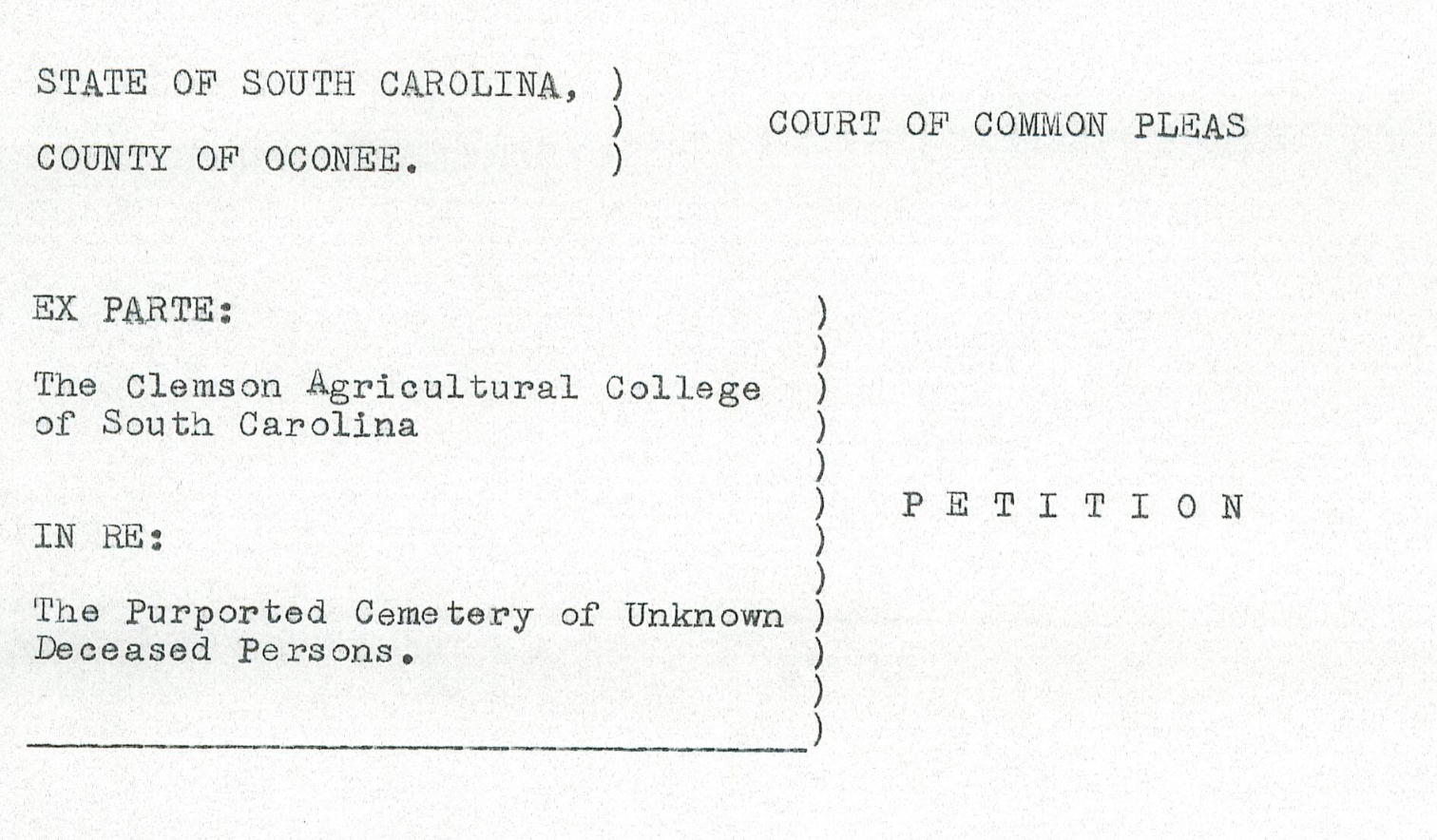

On August 22, 1960, Clemson College petitioned the Oconee County court for legal permission to disinter remains thought to belong to African American enslaved persons and convicted laborers in graves marked by field stones if they came across them in the west side behind the Calhoun family plot and reinter them in the south side of the cemetery. Clemson stated they needed this legal permission for the "orderly and proper development of the campus" and to "excavate and grade the same to be suitable for its corporate purposes." Robert C. Edwards, the President of Clemson College at the time, signed the petition. The judge, J.B. Pruitt of the Tenth Judicial Circuit, ordered Clemson to put ten days’ notice in local newspapers stating that if anyone knew of someone or had family buried in the cemetery and had reason to stop the planned disinterment, they should come to the courthouse on a certain day and time to state their case. According to the court order, no one came forward.

On September 3, 1960, the judge granted Clemson’s request. He stated that, “as a general rule, a body cannot be removed from its place of burial without the consent of the next of kin,” but no one had come forward to object to the disinterment. Removal of remains was permitted for “good cause shown,” which Clemson had apparently demonstrated. Lastly, a law permitted the removal of burial remains “before flooding by water-power pond.” Clemson was therefore “authorized to make exploration to determine whether evidence exists that persons have been buried in the area on the Western slope of Cemetery Hill…” If remains were found, it was the responsibility of the college to disinter and reinter the remains with a licensed embalmer to an area 300 feet to the south of the original field stones, mark the reinterred graves with the same stones, and mark the area of reinterment.7 It is not clear if any remains were moved from behind the Calhoun family plot.

Corps of Engineers Site Plan, May 1960, Robert C. Edwards Papers, Series 11, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

State of South Carolina, County of Oconee, Court of Common Pleas, Ex parte: The Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina, In Re: The Purported Cemetery of Unknown Deceased Persons, Petition, August 22, 1960, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries

Aerial View of Clemson Memorial Stadium and Clemson College Campus, Fall 1960, Clemson University Photographs, Series 100, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

On September 13, 1960, about two weeks after the court order was issued, Clemson College signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the Nello L. Teer Company to clear and grade land in the western area of Cemetery Hill. Between 100,000 and 300,000 cubic yards of dirt were to be removed from that area, likely for the construction of the dikes.

While the construction crew was working, they came across burial remains. Two experts were called in, H. D. Webb, a toxicologist, and Robert Ware, a Clemson zoology professor, to examine the remains. They examined three to five burials in detail and concluded that the remains were of African American children, who were purportedly reinterred in the south side of the cemetery.8 The two dikes were finished in 1961, the same year Harvey Gantt first applied to Clemson, and the Army Corps finished the Hartwell Dam project in 1963. Clemson turned the leveled area of Cemetery Hill into athletic playing fields and a parking lot.9

Explore Cemetery Hill Before and After Hartwell Dam and the 1960 Court Order

SC USDA, Aerial Photograph of Pickens County, 1951, Government Information and Maps Department, University of South Carolina Libraries.

Aerial View of Campus, 1965, Mss 166, Box 32, Folder 685, Donald Bennett Stafford Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, construction on Memorial Stadium and parking lots impacted Woodland Cemetery. When the south upper deck was built in the late 1970s, Press Road was pushed back onto the northern slope of the cemetery. Today it meets the concrete pathway where numerous unmarked graves were recovered under the pavement. In 1980, the area near the entrance of Woodland Cemetery on Williamson Road was leveled to create a new IPTAY parking lot. Additionally, Clemson fans tailgated in Woodland Cemetery near Memorial Stadium, or Death Valley, until 2020 when the practice was prohibited.10

To learn more about the changes in the landscape of the cemetery, explore the Visual History.

Aerial View of Memorial Stadium, ca. 1974, Athletics Communications Records, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

Expansion of Woodland Cemetery

In 1989, the Clemson University Board of Trustees updated the policies for Woodland Cemetery that had been in place since 1924. Those eligible for burial included full-time university employees who had worked at the institution for a minimum of five years and their immediate families, including retired employees who met those requirements, and members of the Board of Trustees and their immediate families. Families were responsible for maintenance of their plots, and the University was responsible for maintaining the whole site. The trustees did not recommend expansion beyond the existing 202 plots at that time.11

In 1991, the Clemson Board of Trustees again revised the policies for Woodland Cemetery. The minimum length of service for full-time employees was increased to ten years. Among other revisions, the trustees changed course from their 1989 policy that stated that there were no plans for the expansion of Woodland Cemetery.12 Carrel Cowan-Ricks, an African American archaeologist, was hired by the Department of Historic Houses and College of Architecture at Clemson to help survey the site to allow 100 more burial plots. During the survey work, she conducted a partial excavation of the western slope of Cemetery Hill seeking any unmarked burials of enslaved individuals. By 1993, when no definitive evidence of burials had been found, the University expanded Woodland Cemetery and released burial plots for assignment on the western slope of the hill.13

Copy of Woodland Cemetery Map, ca. 1991, Mss 366, Papers of Carrel Cowan-Ricks, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

In December 2000, Clemson University President James F. Barker established the Woodland Cemetery Stewardship Committee to devote special care and attention to the sacred and historic site. The Stewardship Committee enacted several repairs and improvements and oversaw the construction of the main stone gate, forecourt, and stone retaining walls through fundraising efforts with alumni and current and former faculty and staff. The Stewardship Committee produced a series of biographies and public interest stories about Clemson founders and key faculty in The Clemson World to promote renewed interest in the long-term preservation of the cemetery.

In 2002 and 2005, the state archaeologist conducted ground penetrating radar (GPR) surveys at the cemetery. In 2002, “wet soil conditions prevented conclusive findings in the western slope." In 2005, the archaeologist reported that “no burials were identified” in the area west of the Calhoun family plot where Professor Cowan-Ricks had excavated in the 1990s, but there was evidence of burials in the south slope.14 Given this GPR information, the University expanded the cemetery to the northwest and west, setting the current boundaries. In 2005, the Board of Trustees also changed the eligibility requirements for burial, increasing the minimum years of employment at Clemson to 20 years. The Stewardship Committee has been less active since President Barker retired and has not met since 2018. The African American Burial Ground, A. P. Calhoun Family Plot, and Woodland Cemetery Historic Preservation Project has been created to continue their efforts to create a long-term preservation and memorial plan for all burials in the cemetery.

Brochure for the Woodland Cemetery and African American Burial Ground, 2022, Clemson University Creative Media Services.

Citations

- Cemetery Committee to Walter Riggs, May 17, 1923, Series 17, Box 23, Folder 269, Walter Riggs Presidential Records, Correspondence, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

- Samuel B. Earle Series 16, Box 3, Folder 46, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

- Clemson Board of Trustees, Trustees Minutes, July 4-5, 1922, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/trustees_minutes/390.

- A Report on Woodland Cemetery, December 5, 1957, Mss 366, Box 2, Folder 17, The Papers of Carrel Cowan-Ricks, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

- J. C. Littlejohn to A. C. Lee, November 4, 1940, Series 87, Box 20, Folder 11, Office of the Vice President for Business and Finance Records, Stadium Construction, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries; Jerome Reel, The High Seminary Volume 1: A History of the Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina 1889-1964 (Clemson, SC: Clemson University Digital Press, 2011), 292-294. Jermaine Johnson contributed to this research in the Spring 2022 Creative Inquiry class for the cemetery.

- Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina, Chronology of Hartwell Dam Project, 1949-1956, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries; “$2.1 Million to Protect Clemson Campus, Contract for Seneca River Diversion Let,” The Greenville News (Greenville, SC), June 28, 1960; Jeno Palotai, Map, August 19, 1960, Oversize Folder OV1, Mss 366, The Papers of Carrel Cowan-Ricks, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries. Undergraduate Research Assistants Lucas DeBenedetti and Nolly Swan contributed to this research.

- State of South Carolina, County of Oconee, Court of Common Pleas, Ex parte: The Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina, In Re: The Purported Cemetery of Unknown Deceased Persons, Petition, 22 August 1960, and Order, 3 September 1960, Box 2, Folder 17, Papers of Carrel Cowan-Ricks, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

- Memorandum of Understanding between Clemson and Nello L. Teer Company, September 13, 1960; Interview with H. D. Webb, 18 September 1991, Box 2, Folder 17; and Interview with Robert Ware, 1992, in Mss 366, Papers of Carrel Cowan-Ricks, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

- Joseph C. Ellers, Getting to Know Clemson University Is Quite An Education: Determination Makes Dreams Come True (Clemson, SC: Blueridge Publications, 1987), 35-43; Hartwell Dam and Lake History, US Army Corps of Engineers, https://www.sas.usace.army.mil/About/Divisions-and-Offices/Operations-Division/Hartwell-Dam-and-Lake/history/.

- Matthew Sloop, Alexis Thomas, and Destiny Stewart contributed to this research in the Spring 2022 Creative Inquiry class for the cemetery.

- Woodland Cemetery Policies and Procedures, September 22, 1989, Woodland Cemetery Policies and Procedures 1924-2009, Series 613, Woodland Cemetery Stewardship Committee Records, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/woodland/6/.

- Woodland Cemetery Policies and Procedures, July 12, 1991, Woodland Cemetery Policies and Procedures 1924-2009, Series 613, Woodland Cemetery Stewardship Committee Records, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/woodland/6/.

- Sonya Goodman, Memo to Individuals on Woodland Cemetery Waiting List, March 15, 1993, Series 613, Woodland Cemetery Stewardship Committee Records, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.

- Woodland Cemetery Stewardship Committee, Annual Report, March 15, 2003, Series 613, Woodland Cemetery Stewardship Committee Records, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries; J. Leader, Ground-Penetrating Radar Analysis, Clemson University Cemetery, February 11, 2005, Series 613, Woodland Cemetery Stewardship Committee Records, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=woodland; Correspondence, Papers of the Office of Historic Properties, Series 360, 2002: Box 5, Folders 18 and 19, and Box 13, Folder 22; see also Box 6, Folder 2, and Box 13, Folder 22, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson University Libraries.